Cool Girl Crisis: Why Dissociative Feminism May Actually Be Anti-Feminist

*Article from Lexington Line’s Autumn/Winter 2022 Issue, pages 32-34

Check out the full issue here

We all know her...

The girl surviving day after day with a cigarette in her mouth, last night’s smokey eye makeup smeared underneath her waterline, and wired earbuds playing The Smiths, Fiona Apple, or Lana Del Rey into her busily pierced ears.

She may be running late to pilates in her coquette-inspired outfit on nothing more than a latte. Instead of music, maybe she’s listening to the Red Scare podcast.

Regardless, she is unhinged, self-destructive, and above all, a nihilistic “dissociative feminist,”—a term coined by BuzzFeed writer Emmeline Clein in her 2019 article “The Smartest Women I Know Are All Dissociating.”

The archetype isn’t new. Heroin chic was all the rage in the ‘90s, and the Tumblr era of 2014 brought on the spread of #thinspo and pro-ana (pro-anorexia) content that undoubtedly harmed young women. The issue is that many saw the problem and figured this was over.

With TikTok’s new swiping feature, however, there has been a drastic rise in the romanticization of serious mental health issues. TikTok has taken a step that Tumblr didn’t by suggesting contacts for the National Eating Disorder Association when one searches terms like #proana.

But what’s worse? Unlike Tumblr, these dissociative takes can show up unsolicited on your “For You” page.

Photography: Davide Sorrenti

“This is heroin, this isn’t chic. This has got to stop, this heroin chic.” - Ingrid Sischy at Sorrenti’s wake

Dissociative feminism can be dangerous both privately and culturally. Getting through the days by dissociating into this archetype, and smirking at your own silence can whittle away your sense of self worth while empowering oppressors.

I will admit, I’m not innocent. I have found myself in moments where it was easier to dissociate from the frustration inherent in every feminist issue. Even though these videos create a knot in my stomach, the repost button taunts me every time a romanticizing take on mental health enters my feed.

Tragicomic antagonists feeding the dissociative dream are plastered all over the media world: Fleabag, Amy Dunne, the unnamed protagonist in Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, and countless others. Most of these women are idolized for their personalities, and while some of them have admirable qualities, they all have something in common: “female rage” that wallpapers over women’s mental health issues.

“The death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.”

But if you stop drooling over the romantic TikTok edits of raging white female characters set to Radiohead’s “No Surprises,” over femcel TikTokers expounding on their desire to be a messy girl, you might realize something.

If you are a “dissociative feminist,” you are privileged in one way or another. In many cases, you are a white, slim, and conventionally pretty woman with the ability to levy sarcastic, impassive takes when speaking about feminism.

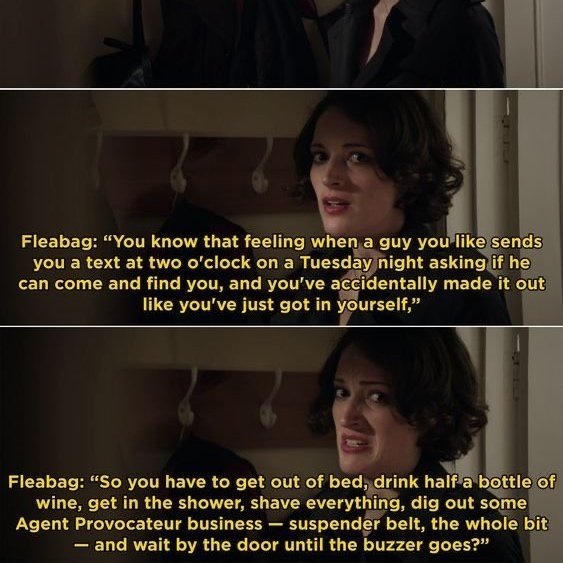

Take a look at Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s tragicomic protagonist, Fleabag, for example. You’ve most likely heard of her and possibly even desire something like her ironic personality. In case you haven’t heard of it, I will catch you up quickly.

Fleabag, as the unnamed character is called, turns her moments of tragedy into comical derision aimed at herself.

Fleabag often breaks the fourth wall to joke about her situation, all in the name of dissociation. It is as though she is watching herself from outside her body, using sarcasm to suppress feelings that stem from the cultural pressures imposed upon women.

Fleabag is the cool girl; her desires don’t clash with his because she is usually pretending to be exactly the woman men want her to be. She does wrong, but in our eyes they are just mistakes, human mistakes. I will admit, I too wanted to be like Fleabag at one point.

Dissociative female characters are viewed subjectively. They feel familiar and relatable, even when they do something objectively wrong. But when we look at reactions to POC characters that make similar choices, reactions suddenly become objective, based on moral rights and wrongs.

Devi from the Netflix series Never Have I Ever is an imperfect protagonist. Media response to Devi, who is only 15, has included headlines like “Ranking The Characters In Netflix’s Never Have I Ever From Least Shit To Devi.”

Devi is unpopular, which she blames on her Indian background. But once Aneesa, another Indian character, is clearly “likable in spite of her brownness,” Devi has no excuse, Emaan Haseem, a Pakistani woman told me by email.

“Of course Devi is flawed, but she’s real. Real in that, though many brown girls may not want to admit it, we experience the same anger, frustration and jealousy that Devi feels day-to-day,” she says.

I recently came across a TikTok using the Kali Uchis song “After The Storm” over a montage of some favorite “female rage” characters. From Amy Dunne to Alaska Young to Cassie Howard to Jennifer Check to Maxine from X to Black Swan’s Nina Sayers, I am ashamed to say it took me seeing a duet made by Emaan Haseem to realize something—every woman was white.

WOC are “not viewed as poor, sad or fragile, let alone dissociative (the themes that these edits follow carefully by depicting the white female characters’ breaking point),” Emaan says. The unique trait of these “female rage” characters, she says, is whiteness.

“Throw in Abileen Clark’s ‘Eat my shit’ scene from The Help in one of these edits,” she continues. “How about replacing a Lady Bird mother daughter scene with Evelyn and Joy Wang’s conversation about homosexuality and acceptance. Maybe even include Devi’s Aneesa-induced breakdown. It doesn’t feel right.”

What’s “unique and defining” about the original dissociative aesthetic isn’t that it’s about upset women— it’s about upset white women, she says.

“Because in the States, at least, WOC representation will always have to address the complexity of their unique racial experience,” she says. “And well, that doesn’t really fit an aesthetic does it? Certainly not the dissociative feminist one. It would be far too complex.”

Outside of the chronic misrepresentation inherent to the “female rage” archetype, there are a multitude of other dangers.

Maybe you are using TikTok to address your depression, or your eating disorder, or your crippling OCD.

“In more impressionable years, the dissociative attitude would paint a very depressing world view,” Emaan says. Maybe this is your tactic for coping, for being ‘relatable.’ I am not saying the dissociative dream women on social media are all at fault for this, that would just be me dissociating from our reality.

Source: Pinterest

But in many ways, our society has pushed us to glorify mental health disorders, eating disorders, the use of drugs, and more.

Look back at the controversial subject of Euphoria and all of the rage over whether the director was feeding young adults a look into the normalization of sex and drugs while glorifying disorders such as bipolar disorder. Or if you are around my age, you may remember the release of 13 Reasons Why and your parents sitting you down to ‘talk’ after hearing about the spike in suicide rates.

Young and impressionable, we begin to contribute to normalizing potentially toxic media and share it with the world.

Alina Arseniev-Koehler of the University of Washington and Seattle Children’s Research Institute conducted a study with researchers to investigate “Pro-Eating Disorder (ED) Twitter profiles’ references to EDs and how their social connections (followers) reference EDs.”

Slightly over 36 percent of pro-ED profiles had ED references, while 45 percent of the combined total followers had mention of an ED on their personal profiles. This among many other studies proves the harm that can be caused by dissociating and nonchalantly mentioning such topics in a TikTok while Lana Del Rey breezily sings “you’re just a man.”

On the more facade-encouraging sides of social media, women are dissociating for other purposes. Nevertheless, there are multiple forms of dissociation women are using to escape from the reality of our society.

From a young age, we detach from our authentic selves to curate our online presences, most times in the male gaze. We ask ourselves various questions when posting on social media: What will make me relatable? What will make me desirable? What will make other women fume with jealousy?

Don’t mistake me, I am not telling you who or how to idolize. As humans we are impressionable, and that is a trait we can’t always control. But next time you notice the knot in your stomach or the sweat glazed across your forehead, don’t float above your body in an attempt to ignore it like Fleabag.

Reoccupy your body and realize the dissociative dream you once thought of as heaven will only move our society further into the realities you are avoiding.