Remembering Us: How to Deal With Excessive Nostalgia

*Article from Lexington Line’s Spring/Summer 2022 Issue, pages 18-19

Check out the full issue here

With shaky fingers, I open the small red notebook that has haunted me since the day I found it in a basement storage bin. I know what’s in there, and I know it’s going to hurt to read it. But without a pause, I open it and let in words my grandmother wrote more than twenty years ago.

Source: British Foreign Policy Group

Her sloppy script comes to life, creating a continuous flow with each turn of the page. My cheeks turn scorching hot, causing droplets to fall from my eyes. And suddenly, I am outside my own body, watching Annamarie Accardi go through life.

“I loved to go to Woodstock with my friends, even though we never made it past the parking lot,” the diary reads. She lived a whole life before we knew each other, I realized. We all live whole lives that, even if they are recorded, at some point are gone for good.

I find myself dwelling on my past more than I should. I could be listening to a song, scrolling through my camera roll, or finding a stuffed animal I used to cherish. It doesn’t make me happy, but I willingly throw myself into the past to try and feel a few things twice.

Maybe you do this too. We all have moments that we wish to forget or that we would relive because they made us so happy. The best we get is a simulation of that feeling.

I’ve never truly gotten over the loss of my grandmother. I can still hear the ambulances scream down my block. The red and blue flashing lights haunt me when I close my eyes, and I am left with nothing but knick-knacks around my house to remember her by.

In the 1600s, a physician named Johannes Hofer coined the term “nostalgia.” The British Psychological Society says that he associated the term with anxiety, homesickness, and disordered eating.

Keeping objects or images from one's childhood can make you nostalgic. But there are no rules to this feeling; you can be nostalgic about something that happened yesterday.

Source: MarketingWeek

This can be extremely harmful to your mental health, as it has been to mine. Just like a drug addict chases their first high, I chase and chase the feelings I experienced at different points in my life, knowing it won’t fulfill me.

In an episode of the podcast “Speaking of Psychology,” Dr. Krystine Batcho, a professor of psychology at Syracuse University, calls this conflict “bittersweet.”

“It's sweet because we're remembering the best times, the good times of our life. The bitterness comes from the sense that we know for sure that we can never really regain them, they're gone forever,” she says.

This longing for the past is nothing new. The ancient Greek poet Sappho shared these ideas in her work in the 6th century BCE. Through her words, she is able to encapsulate the immensity of this feeling.

I was so happy

Believe me, I

prayed that that

night might be

doubled for us

Source: World History Encyclopediapedia

Sappho gives the impression that she is pleading with the addressee or a higher power to go back in time—knowing that cannot happen. By capitalizing the word “Believe,” she tries to convince the audience, and herself, that she was truly happy at that point in her life. This creates the bittersweet feeling Dr. Batcho describes.

Our memories are ours after all—and they are not always happy. But even if they are, our memories serve as a reminder that we might never feel those exact emotions again.

Though experts today do not consider nostalgia to be a mental illness, it does not always come with a positive connotation.

“Longing for the past (something you can’t reclaim) can fuel dissatisfaction with the present,” Crystal Raypole says in a Healthline article. “Nostalgic depression, then, can describe a yearning colored with deeper tones of hopelessness or despair.”

At ten years old, I lost the love of my life. The moment I lost her, I didn’t realize how much her absence would affect me all the way into my adulthood.

The one thing I’m able to fill the void with is objects. Have you ever looked at something that reminds you of someone, and somehow there you are, watching yourself with this person, kind of like a ghost?

Whenever I see a teacup (of any size or design), I’m transported to Sunday mornings sitting around my grandmother's coffee table. We’re either watching I Love Lucy on repeat or singing Michael Buble’s very underrated single “Home” around the kitchen.

The sunlight hits whatever hair color she was sporting that week, and the soft glow illuminates her porcelain skin. I am happy. She makes me laugh.

Then I realize I’m not there and I never will be again.

A red Volkswagen bug probably means nothing to you—but that small car means the world to me. My grandmother was a woman of a particular taste, to say the least. She loved wearing brooches, specifically ladybug ones to match her car.

The life of a fifth-grader is not easy, and once after a long day, my grandmother and I decided it was necessary to blow off some steam, with a view of course. We headed to the beach five minutes from our house and let the saltwater stench tickle our nostrils, instantly making us laugh.

Tears roll down my cheek, and they aren’t from giggling. She’s not actually laughing, and I’m in a Ford Escape, not her Volkswagen.

Re-living these memories doesn’t make the pain of her loss any easier, but it is the closest I can get to feeling her presence without actually being in it. I know there has to be a way to deal with it in a healthy way.

Jordyn Kruse, a 21-year-old LIM College student, has kept every birthday card she’s ever received in a box since she was in fifth grade.

“It doesn’t matter if the person is still in my life, we naturally drifted apart, or it’s someone that I had a major falling out with, they were important to me at one point and loved me enough to celebrate me, which feels important,” she says.

Instead of painting black nail polish over the faces of her ex-friend's pictures (fine, I’ve done that), Jordyn has found a way to honor these relationships—even though some of them no longer exist.

“The box is hidden in the back of my closet, so it doesn’t get too much attention. But when I do go through the collection of cards, it’s nice to remember the details about that time in my life I had otherwise forgotten,” she says, “It is definitely more sweet than bitter to return to.”

In a 2012 New York Times article called “What is Nostalgia Good For?,” John Tierney quoted Dr. Clay Routledge, a social psychologist at North Dakota State University.

“We see nostalgia as a psychological resource that people can dip into to conjure up the evidence that they need to assure themselves that they're valued,” he says.

Source: New York Times

To Jordyn’s point, nostalgia can be a reminder of how loved you are. It doesn’t matter if that person is in your life or not anymore because there is no denying that those emotions existed, that you had them to lose in the first place.

Whether we want to accept it or not, life does go on. I find that I try to hide in the past, and you might too, but this can actually prevent you from establishing new connections.

“Managers can take advantage of nostalgia’s social nature to promote strong relationships and teams. Encouraging employees to share nostalgic stories with team members may help them build deeper connections because nostalgia orients people toward social goals,” Routledge says.

Sometimes blasting your radio, looking through pictures, or sifting through nostalgic memorabilia is tempting—but in some cases, it might actually be holding you back from life.

“Instead of thinking about how amazing that career triumph was, think about how it got you to where you are today. Use those past experiences to savor or cope with the present instead of longing for the world that used to be,” Thorin Klosowski, an editor at Wirecutter, says in an article from LifeHacker. “Instead of saying, ‘those were the days,’ and leaving it at that, think about it from a more existential perspective with a question like, ‘what has my life meant since then?’”

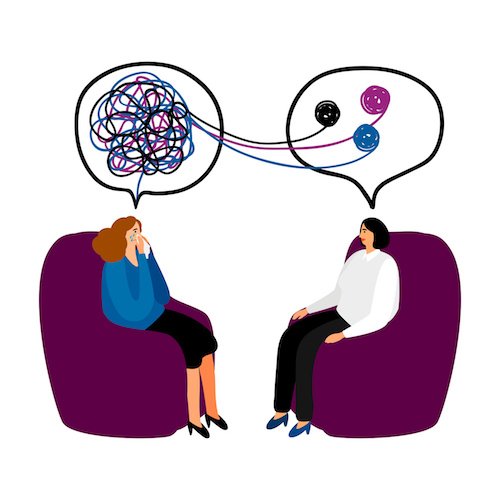

Sometimes I feel like I cannot express this longing for the past to the people around me, but that is why there is therapy. Going to therapy has given me an outlet. Nostalgia can be harmful when it’s dealt with in an unhealthy way. This is not to say that you cannot honor the past, but relying too much on objects and images or anything that makes you nostalgic can be harmful. Trust me, I would rather take any memorabilia from my grandmother's life than have nothing at all. However, it is important to make sure it does not become an addiction.

Source: NAMI

Personally, I feel that one of the fears that stem from my excessive nostalgia is that I will forget about my grandma. But, that's not true. There are so many more things to be nostalgic about, like watching my baby cousins be born and grow right after she passed.

That is to say: if possible, take a wide view and achieve something like nostalgia for something as it happens. Then let it live there.