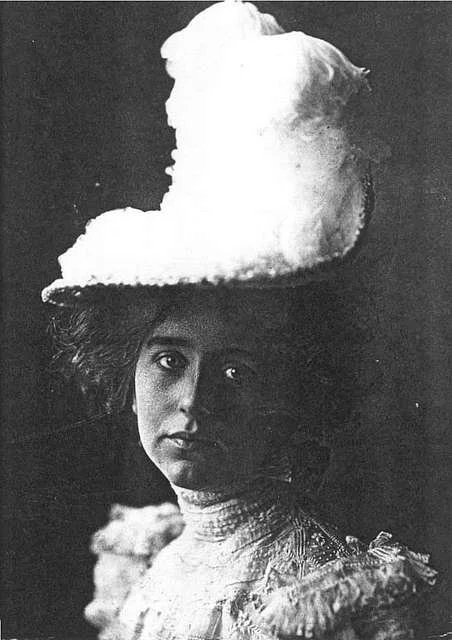

The Woman that Started it All: Natalie Clifford Barney

A poorly lit room full of people in eccentric clothes, an alcohol table at the center of the space, music coming out of a corner, and friends dancing till late on a Friday night. What might sound like your typical frat party was actually known as a “Salon” in the early 1900s.

Every Friday night, Natalie’s apartment was filled with the most talented writers, poets, dancers, artists, singers, and creatives of the time—to share a glass of wine over their favorite prose.

Source: Picryl

While Salons have been around since the 16th century, there is one specific woman we can thank for making them popular in the 1900s, and her name is Natalie Clifford Barney.

Born in Ohio 1876, Natalie was the daughter of a wealthy car manufacturer, who sent her to do her studies at a French boarding school—where she got to immerse herself in the world of art and creatives.

From a young age, Natalie was described as witty, rebellious and independent. She claimed her “first adventure” was at five years of age with none other than Oscar Wilde, who—after telling one of his stories to her—inspired and changed Natalie’s life trajectory forever.

Miss Barney began her career by publishing under the pseudonym “Tryphe.” She chose to maintain anonymity because in 1900 her father bought and burned the full stock of her first published book, after finding out about the lesbian themes brought up within it.

Said father passed away in 1902, leaving all his inheritance in Natalie's name, who used the money to settle down in Paris and gather a community of artists—that she invited to “Rue 20 Jacob” every Friday night to share artworks and analyze the current state of the world. In this Latin Quarter apartment where, “the lost generation found not just a safe heaven to be weird but a temple for friendship,” is where the “Temple d’amitié” was born.

Source: Picryl

Natalie’s house was described as an aquarium—with underwater lighting, no natural sunlight, chairs covering the space, and people in every corner. They hosted from 20-100 people weekly, where her mother attended the artists and Natalie personally took care of the writers. Some of the most recognized works and artists today, walked through those doors and spent a night dancing till late in the A.M.

Source: Picryl

Natalie believed that artists from the United States, France, and Britain should know one another and translate each other's work—she invited many American creatives to her Friday salon who helped bring the practice back to the American continent.

She also used her inheritance to help struggling artists, and form 'L’Academie des Femmes' in 1927 to provide education for young girls—particularly in rebellion against 'L'Academie Française,' which only accepted male students.

Source: Picryl

Unfortunately, in 1960 the Salon had to stop due to the war—Natalie took refuge in Italy. While the doors reopened, the Salon lifestyle never regained its former vibrancy after the war.

Natalie always knew who she was and stayed true to herself; She was a proud non-monogamous lesbian, a feminist, an experimenter of life who once commented that, “if I had one ambitious is to make my life itself into a poem.”

She was someone who never stopped fighting for what she believed in; she founded a prize in honor of her ex-girlfriend Renee Vivien’s; and managed to make 'The Temple d’amitié' a landmark for the arts, one that could not be altered by new owners.

In 1972, she died in Paris at the age of 96. She left behind an unmatched legacy, an open pathway for future women in creative fields, and the famous last words “Je suis cet être légendaire où je revis” (“I am a legendary being in which I will live again”).